Publications

How can we answer the most difficult questions?

Imagine an engineer from a car manufacturer comes to his Board of Directors with one simple question. "We have good news, the self-driving car outside is ready! However, we still have to make one choice. In the most extreme situation that the car has to intervene, does the driver die or the kind that stands in front of the car?" What do you do as the person with ultimate responsibility to answer that question?

This question is impactfull, how are you able to make such decision? Mercedes did it in ’14 and the German government answered this question also, two years later. Interesting result was that the outcome was complete the opposite.

My interest was started. What did they do in the boardroam, how did they make their decision? Did they use the Socrates methodology? Or did the use the Dilemma method or the Utrecht model as we are familiar with in the healtcare sector for answering moral and ethical questions?

Today, how to answer such a question is increasingly relevant in combination with developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI). This development means that the difficult questions may not be different, but must be made very explicit, because the AI Robot will act “on behalf of” us. And if we don't even know how to answer such a question, how do we transfer responsibility to AI Robots, who will act on our behalf.

Learn from eachother

Recently, for my E-MBA, I was able to do an initial research for answering this question: how do we answer the most difficult questions? The ethical questions. Which process do we go through? Are we going through a process at all? Can you go through a process for answering ethical questions or is it inherent in these kinds of questions that your own moral awareness must be leading in answering?

Discussing this issue resulted in most interesting conversations, but often also a surprising outcome, namely; no idea how we can answer these kinds of questions in a correct manner. The healthcare sector seems to be at the forefront, rightly so and understandably. There, tough choices are made every day that require a good assessment, choices that sometimes concerns life and death. What can we learn from them? Where can we improve our processes?

The ethical challenge in the financial sector?

In the financial sector we see important and good developments, we make agreements about our behavior (think specifically of the bankers oath), we see the development of moral compasses, the establishment of ethical committees, etc. Unfortunately, we also see these developments being necessary when we realize that there is little fertile ground for confidence in the sector. Reputation was tainted by immoral unethical behavior where self-interest sometimes preferred over customer or participant interests. It is precisely in this sector where trust is most crucial that we have to make make a difference if we try to make our choices as well as possible and are able to explain our choices appropriately, even the most difficult ones.

How do you do that?

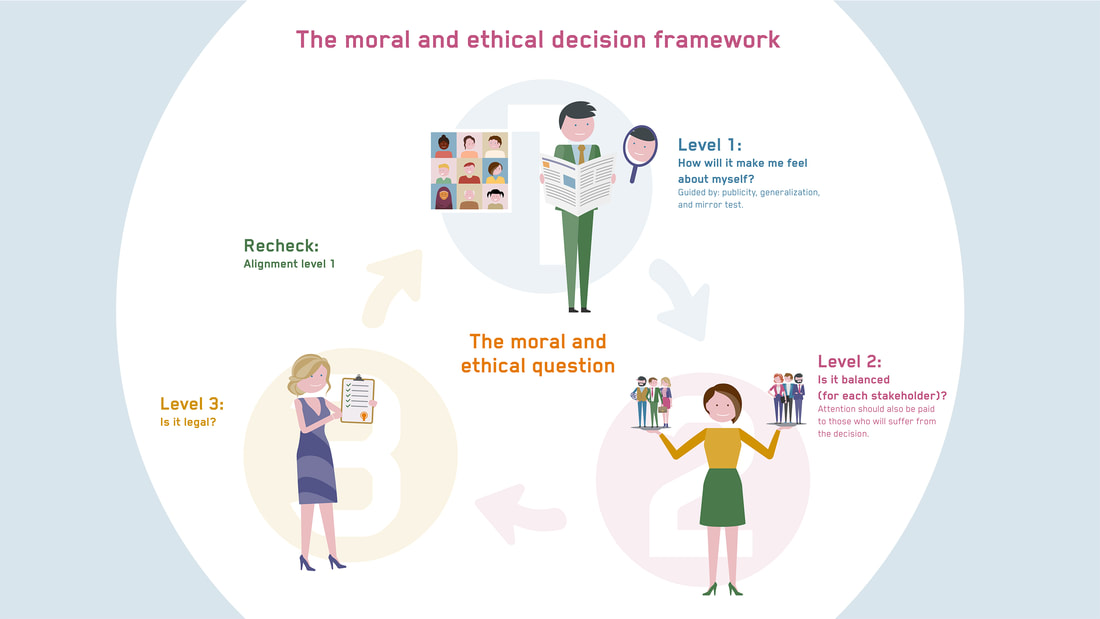

During the research I came across the three ethical check questions from Norman Vincent Peale and Kenneth Blanchard. Simplistic in its simplicity, at the same time intriguing in its dimension. On three levels, a person is asked to consider a ethical issue. From the legal framework (is it legal?), from the balance perspective (is it balanced?) and by challenging our feeling (how does it make me feel about myself).

An interesting connection is made with the three words that are known from Aristotales: logos, pathos and ethos. The links with legal, balanced and feeling are therefore easy to connect. Another relevant aspect for the further research, in combination with the impact of AI, was that you could use data at multiple levels. This was an approach that gave sufficient reason for further research of these three questions.

In collaboration with two professors and four experts, we started a Delphi study to deepen these questions and see whether that example from 1988 has still its relevance in practice Today.

And the first answer is yes, together with an "update"

The first research result was clear. Yes, this approach is valuable to use in daily life to answer the most difficult questions. However, it does require an update and some fundamental adjustments.

Level 1: how does it make me feel about myself?

The research has shown that when answering these questions, the emotional aspect is particularly important, such that further research was necessary and requires a different prioritization in the order of questions. Deepening the question is possible by the support of the publicity test, generalization test and mirror test. With three in-depth questions you can make the emotional issue more objective. Actually, your feeling is not objective. When answering, it is also important that you start the slow thought process in your consideration. So not only your quick intuitive part of your brain, but the combination of both is relevant in this.

Level 2: Is it balanced (per stakeholder)?

Also in terms of balance, it is important to deepen and reflect on the issue, for whom is this choice actually balanced? Who are the relevant stakeholders in this issue? An important nuance in this respect is that if you are working on answering this issue from the various stakeholders, a recheck is important at this level. Namely, specific attention to those who suffer from this issue. Not by definition with the aim to compensate them, but to raise awareness of this vulnerable group. Because of the primary focus on the outcome of the answer, this important group could possibly be skipped.

Level 3: Is it legal?

The last level is the legal check. Is it legal? This has to be answered from the perspective of legislation, but possibly also from the perspective of established frameworks of the company for which you work. It is interesting to note that Peale and Blanchard started with this issue and after further research we want to end this very consciously. Why? You could simply say that if you start answering this question from the legal framework, you will automatically fall into the trap that the legal framework may be too restrictive. It is precisely in the combination with AI that we see that it is important to look further than Today. Developments on AI are rapidly and the legal framework can hardly keep up. This could mean that if you start with this issue from the current framework, you automatically run behind the facts instead of ahead.

Recheck: Is it stil in accordance with level 1?

And yet a final final check has been added. Very conscious. If you have completed all three levels, the final check is whether the outcome at the last level is still in line with the first. In this way, you secure the beginning and end process by means of an integral linked chain.

The overview below presents the ethical framework for decision-making. This concerns the simplified model. The study went one step further with the impact of AI. For example, where could we use AI to better answer these questions from data that we add to our analysis with the help of AI Robots.

Continuing in a PhD research

In the meantime it has become increasingly clear to me that I do not want to let go this theme and I am most pleased to be able to start a PhD research.

The subject inspires me, and I realize that this first step was just a first stepping stone that requires further steps. The theoretical model requires more depth, requires analysis of concrete practical experiences, and also offers opportunities to analyze whether AI can actually fulfill phase 2 & 3. But for me also the ambition to create broader support and impact and thus prevent it from remaining merely an academic reality and not having any concrete application.

Ultimately, it is the dialogue that is the main focus to moral ethical leadership. In the publication below you can read more about the first study, physical copies are also available upon request.

Imagine an engineer from a car manufacturer comes to his Board of Directors with one simple question. "We have good news, the self-driving car outside is ready! However, we still have to make one choice. In the most extreme situation that the car has to intervene, does the driver die or the kind that stands in front of the car?" What do you do as the person with ultimate responsibility to answer that question?

This question is impactfull, how are you able to make such decision? Mercedes did it in ’14 and the German government answered this question also, two years later. Interesting result was that the outcome was complete the opposite.

My interest was started. What did they do in the boardroam, how did they make their decision? Did they use the Socrates methodology? Or did the use the Dilemma method or the Utrecht model as we are familiar with in the healtcare sector for answering moral and ethical questions?

Today, how to answer such a question is increasingly relevant in combination with developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI). This development means that the difficult questions may not be different, but must be made very explicit, because the AI Robot will act “on behalf of” us. And if we don't even know how to answer such a question, how do we transfer responsibility to AI Robots, who will act on our behalf.

Learn from eachother

Recently, for my E-MBA, I was able to do an initial research for answering this question: how do we answer the most difficult questions? The ethical questions. Which process do we go through? Are we going through a process at all? Can you go through a process for answering ethical questions or is it inherent in these kinds of questions that your own moral awareness must be leading in answering?

Discussing this issue resulted in most interesting conversations, but often also a surprising outcome, namely; no idea how we can answer these kinds of questions in a correct manner. The healthcare sector seems to be at the forefront, rightly so and understandably. There, tough choices are made every day that require a good assessment, choices that sometimes concerns life and death. What can we learn from them? Where can we improve our processes?

The ethical challenge in the financial sector?

In the financial sector we see important and good developments, we make agreements about our behavior (think specifically of the bankers oath), we see the development of moral compasses, the establishment of ethical committees, etc. Unfortunately, we also see these developments being necessary when we realize that there is little fertile ground for confidence in the sector. Reputation was tainted by immoral unethical behavior where self-interest sometimes preferred over customer or participant interests. It is precisely in this sector where trust is most crucial that we have to make make a difference if we try to make our choices as well as possible and are able to explain our choices appropriately, even the most difficult ones.

How do you do that?

During the research I came across the three ethical check questions from Norman Vincent Peale and Kenneth Blanchard. Simplistic in its simplicity, at the same time intriguing in its dimension. On three levels, a person is asked to consider a ethical issue. From the legal framework (is it legal?), from the balance perspective (is it balanced?) and by challenging our feeling (how does it make me feel about myself).

An interesting connection is made with the three words that are known from Aristotales: logos, pathos and ethos. The links with legal, balanced and feeling are therefore easy to connect. Another relevant aspect for the further research, in combination with the impact of AI, was that you could use data at multiple levels. This was an approach that gave sufficient reason for further research of these three questions.

In collaboration with two professors and four experts, we started a Delphi study to deepen these questions and see whether that example from 1988 has still its relevance in practice Today.

And the first answer is yes, together with an "update"

The first research result was clear. Yes, this approach is valuable to use in daily life to answer the most difficult questions. However, it does require an update and some fundamental adjustments.

Level 1: how does it make me feel about myself?

The research has shown that when answering these questions, the emotional aspect is particularly important, such that further research was necessary and requires a different prioritization in the order of questions. Deepening the question is possible by the support of the publicity test, generalization test and mirror test. With three in-depth questions you can make the emotional issue more objective. Actually, your feeling is not objective. When answering, it is also important that you start the slow thought process in your consideration. So not only your quick intuitive part of your brain, but the combination of both is relevant in this.

Level 2: Is it balanced (per stakeholder)?

Also in terms of balance, it is important to deepen and reflect on the issue, for whom is this choice actually balanced? Who are the relevant stakeholders in this issue? An important nuance in this respect is that if you are working on answering this issue from the various stakeholders, a recheck is important at this level. Namely, specific attention to those who suffer from this issue. Not by definition with the aim to compensate them, but to raise awareness of this vulnerable group. Because of the primary focus on the outcome of the answer, this important group could possibly be skipped.

Level 3: Is it legal?

The last level is the legal check. Is it legal? This has to be answered from the perspective of legislation, but possibly also from the perspective of established frameworks of the company for which you work. It is interesting to note that Peale and Blanchard started with this issue and after further research we want to end this very consciously. Why? You could simply say that if you start answering this question from the legal framework, you will automatically fall into the trap that the legal framework may be too restrictive. It is precisely in the combination with AI that we see that it is important to look further than Today. Developments on AI are rapidly and the legal framework can hardly keep up. This could mean that if you start with this issue from the current framework, you automatically run behind the facts instead of ahead.

Recheck: Is it stil in accordance with level 1?

And yet a final final check has been added. Very conscious. If you have completed all three levels, the final check is whether the outcome at the last level is still in line with the first. In this way, you secure the beginning and end process by means of an integral linked chain.

The overview below presents the ethical framework for decision-making. This concerns the simplified model. The study went one step further with the impact of AI. For example, where could we use AI to better answer these questions from data that we add to our analysis with the help of AI Robots.

Continuing in a PhD research

In the meantime it has become increasingly clear to me that I do not want to let go this theme and I am most pleased to be able to start a PhD research.

The subject inspires me, and I realize that this first step was just a first stepping stone that requires further steps. The theoretical model requires more depth, requires analysis of concrete practical experiences, and also offers opportunities to analyze whether AI can actually fulfill phase 2 & 3. But for me also the ambition to create broader support and impact and thus prevent it from remaining merely an academic reality and not having any concrete application.

Ultimately, it is the dialogue that is the main focus to moral ethical leadership. In the publication below you can read more about the first study, physical copies are also available upon request.

Publications - downloads

| Moral and Ethical Leadership in a Digitalized Financial Industry - Paper | |

| File Size: | 5005 kb |

| File Type: | |

| Moral and Ethical Leadership in a Digitalized Financial Industry - Presentation | |

| File Size: | 837 kb |

| File Type: | |

See for more info and publications also: ResearchGate